As high schools and colleges focus heavily on technology-driven curriculum, finding skilled laborers has become one of the biggest challenges facing local manufacturers.

Burgener’s Woodworking has been in Vancouver since the early 1990’s. They specialize in custom casework and architectural millwork manufacturing for commercial buildings. With 16 employees in-house and six more that handle installs and finish carpentry in the field, familiarity with the tools of the trade is preferred.

“Essentially everyone we bring in, we train to do something,” said Robin Burgener, company owner. “They would’ve gotten experience in vocational classes in high school – building, cabinetry, metal shop, drafting class.”

In Washougal, Mike Burnett owns Orbit Industries, a custom metal fabrication company in business since 1961. He’s particularly frustrated with the recent educational shift.

“Finding skilled employees has been the biggest thing for five years or more. School systems [and] colleges [are] not training people for trade fields,” Burnett said. “I know Boeing has had this problem. That’s why they’re going to states like North Carolina (to hire people) because they’re willing to train people.”

Burnett went on to express his appreciation for technology, but said he sees it as a tool, not the sole industry that should be invested in. He shared that he’s been understaffed for “a good decade” and goes through an inordinate amount of applications to fill positions.

The trend appears to be shifting the responsibility of teaching from schools to employers, which slows productivity and stalls growth. Both Burgener and Burnett’s hiring styles have evolved into focusing on a promising candidate with no practical experience in their respective fields.

The trend appears to be shifting the responsibility of teaching from schools to employers, which slows productivity and stalls growth. Both Burgener and Burnett’s hiring styles have evolved into focusing on a promising candidate with no practical experience in their respective fields.

“[We] look for aptitude, trainability, drive, appropriate work ethic,” Burgener said.

Orbit would like to grow, said Burnett, but due to the unskilled labor force the company has a hard time keeping up with demand and has lost new customers as a result of their backlog. Burnett shared that he has a swing shift staffed with four men that he’d like to put 15 workers on.

Before the downturn in the economy, Burgener had 60 employees. Now that the outlook has improved, the company has had to turn away work. As a result, they’ve chosen to focus their energy on long-standing clients.

A dwindling employment pool for the manufacturing sector is not isolated to Clark County. In the state of California, much has been written about the disappearance of shop class that taught hands-on techniques with wood, metal, rubber and plastics.

According to Burnett, he does have some success when folks relocate from the Dakotas, Texas and Montana, as a result of the oil industry presence. However, he said that he always finds it unfortunate to hire out-of-state workers when there are local people in need of a job.

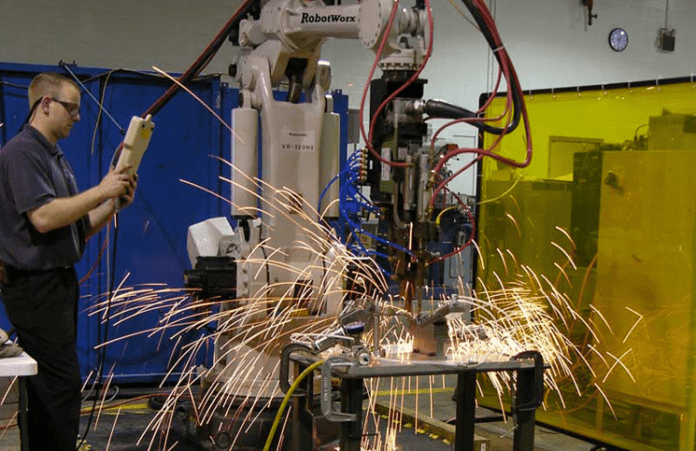

Ironically, a Vancouver-based company created a machine that addresses a facet of the skills required for wood and steel manufacturing through innovative technology.

According to Jack Ragan, vice president of sales and services for TigerStop, founder Spencer Dick was classically trained in cabinet and furniture making.

“He watched employees miss cut, throw things away,” Ragan said. “[He] created TigerStop to build a positioning system where the worker would type in a cut and it’d be right on the mark, accurate, repeatable [and] easy to use.”

Since 1994, TigerStop has built nearly 30,000 machines that are used worldwide, including one in the White House woodworking department that builds stages and sets for a variety of gatherings and functions.

Ragan explained that the TigerStop system was created to fill one need and has since evolved into a machine capable of supporting many industries such as vinyl windows (plastics), cabinet and closet design (wood) and tube and pipe cutting for the oil industry (metal). As a small manufacturing company – TigerStop employs 25 people in Vancouver and another 15 at a second factory in Holland – they are helping colleagues address the labor issue.

“In some ways, TigerStop was born from the need to assist lower-skilled workers,” Ragan said. “A lot of our customers take people who have no woodworking experience.”

The unintended consequence, albeit fortuitous, is that Dick thinks of TigerStop as a software company first and machinery company second. Ragan explained that a great deal of in-house software development occurs daily to adapt the machines to the ever-changing needs and diversity of its customer base. That, in turn, has the potential to attract a younger employment pool to still much-needed manufacturing positions with the promise that there’s “really cool technology to work with in the metal and woodworking industries.”

As Burnett explains it, tech-heavy education is no more the answer than only offering shop classes and trade schools. Like the slow fade of physical education programs, negative effects are inevitable.

“It took us a long time to get here and it’s not going to be an easy fix,” he said. “All of us can’t sit behind a desk and work on a computer.”