BIA President Jack Harroun is currently serving on the city of Vancouver’s Affordable Housing Taskforce along with other BIA members, leaders from the business community, respected nonprofits and city government officials.

As this important conversation unfolds, it has, naturally, spurred related dialogue about the Growth Management Act, driving factors of the housing affordability crisis and the dynamics that play into today’s housing prices.

While we work hand-in-hand with the business and nonprofit community to develop long-term policies to improve housing affordability, I believe now is a good time to develop a broad understanding for all of the elements that contribute to housing prices.

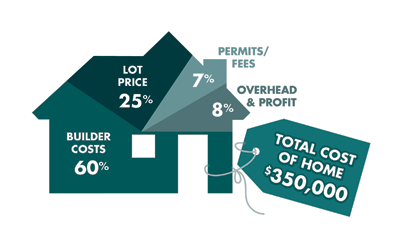

Using a current home in unincorporated Clark County that is on the market for $350,000 there are four primary contributors to the final sales price: builder costs, lot price, fees and builder profit.

60 percent of the house price is attributed to builder costs including materials, labor and, in this example, $12,000 in sales tax on hard costs. The cost of land contributes 25 percent to the price and permits/fees are 7 percent. Builder gross profit on the project is 8 percent, and this includes his overhead costs.

Most of our builders are running about a 7-8 percent profit margin. When you contrast that with standard retail mark-up of 25-55 percent, and consider the tremendous risk involved in developing and building today, you can see that the home building business is not for the faint of heart!

In reviewing detailed breakdowns of a few current housing starts, it is eye-catching to see that the permits and fees line item is the highest single line item on every budget after the land price. Permits and fees include impact fees such as traffic, parks, schools, sewer, system development, plan review and utilities.

In reviewing detailed breakdowns of a few current housing starts, it is eye-catching to see that the permits and fees line item is the highest single line item on every budget after the land price. Permits and fees include impact fees such as traffic, parks, schools, sewer, system development, plan review and utilities.

There is a misperception that new homes don’t pay for themselves and new residents use more services than they pay for in taxes. We believe a careful analysis of the taxes and fees associated with a new home would show that this is not true in Clark County.

40 years ago infrastructure was funded by property tax and spread across the population. During the 70’s and 80’s in rapid growth places like California and Florida, they started asking why new growth was being “subsidized” out of property taxes. Politicians realized that it was easier to charge people relocating to the area that weren’t their voters yet, than to tax voters already in their jurisdiction.

Here in Clark County, property taxes were limited to a 6 percent increase in the 70’s, squeezed down to 3 percent increases in the 90’s and recently capped at 1 percent (allowable increase). While the ability to raise property taxes was shrinking, the county’s responsibilities were growing. Beyond providing roads (which was the historical primary function of Counties), Clark County assumed many charges over the years including the Superior Court system, County jail, trial process, auditor for elections, collecting taxes for local jurisdictions and the assessor’s office – to name a few. And yet paying for these types of services, along with improvements to roads, parks and schools are not just in response to growth, but also as a result of increased pressure from state government as their funding to local governments dwindle.

Generationally speaking, builders share that when their dads and grandfathers were actively building the community around them, they felt there was a social good in helping to provide housing. Today’s builders operate in a highly-regulated environment with the shifted thinking that growth should pay for itself.

In the example I referenced at the beginning of this piece, the lot cost is $88,000. This is inside the Urban Growth Boundary where a shrinking supply of land artificially drives up the price of this very precious commodity. In our county, there are two 20-acre parcels for sale right across the street from each other. The parcel inside the UGB is valued at $10 million and the parcel across the street is $400,000.

In addition to the cost of the dirt, the cost to develop that dirt has skyrocketed. Gone are the days of $2 permits and two pieces of graph paper that are stamped with approval in just one day. To step through all the inspections and regulations like storm water management, it now takes 2-3 years to get a piece of property ready for building. With this longer development lifecycle, market risks increase.

There is no outcry from our industry to return to the days of napkin sketches and limited safety inspections. Our builders care tremendously about community wellness and safety. Some even take an additional step and have third-party verification of their homes’ quality and performance claims.

It is imperative, however, as we collectively wrestle with the issue of housing affordability that we examine history and the line of decisions that have created our current pricing climate. The price of land, extent of our impact fees and the cost to process (in terms of time and money) do lead to a higher priced product for the consumer.

Avaly Scarpelli, Executive Director for the Building Industry Association of Clark County. She can be reached at avaly@biaofclarkcounty.org.